Harold Godwinson is known to history as the last Anglo-Saxon king, the man who lost England to the Normans in 1066. History as tended to see him as a failed monarch, and historians have often been critical of a king who lost his nation after just nine months in power. He has been accused of being power hungry and of seizing the throne without a legitimate claim. He is often described as proud and arrogant, characteristics demonstrated by an apparently rash and disastrous decision to march from York to Hastings in under two weeks to confront the Normans with an exhausted army.

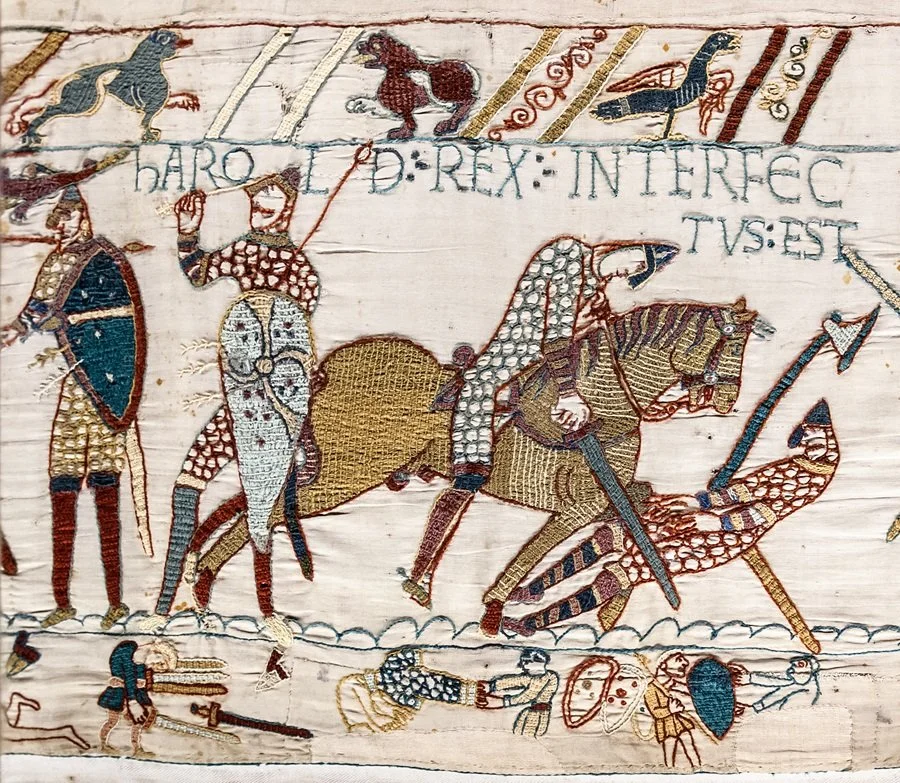

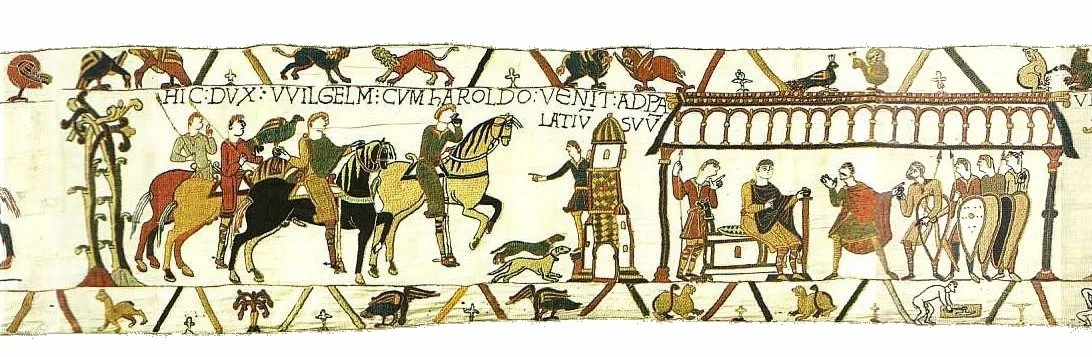

The character assassination of Harold begins almost immediately after William the Conqueror’s victory. Contemporary Norman chroniclers write of an Anglo-Saxon army drunkenly partying on the night before the Battle of Hastings, a reflection, naturally, on their dissolute leader. The same chroniclers tell us that Harold was crowned by an excommunicated archbishop and so his coronation was never legitimate. And the Bayeux tapestry shows Harold as an oath breaker. In fact, in some ways, the Normans attempted to write Harold out of history. The Domesday Book details land ownership at two times; in the time of King Edward and then in the time of the Normans. It does not acknowledge that any other king reigned between these two periods.

But Harold’s character, reign, and his military strategy can all be logically examined to show that Harold was England’s best chance to survive an extraordinarily vulnerable period. Harold also came within hours of being the Anglo-Saxon king who repelled invasions from two of the mightiest warriors in Europe and saved England from conquest.

To understand why this is the case we must examine how England stood in January of 1066 when King Edward the Confessor died without a direct heir. Hostile forces were waiting for this moment, knowing that a potential succession crisis would be the perfect opportunity to invade England. The main threats came from two men, Harald Hardrada, King of Norway, and Duke William of Normandy. Both of these men had formidable martial reputations.

Described by the chronicler Adam of Bremen as ‘the thunderbolt of the North’, Hardrada was exiled from Norway at the age of 15 and spent time fighting as a mercenary commander for the Kievan Rus and the Varangian Guard of the Byzantine Empire. Having become a famous and fabulously wealthy warrior, he returned to Norway and seized the throne. His forceful unification of Norway earned him the soubriquet of ‘Hard Ruler’(Hardrada). In 1066 he also had the support of Harold Godwinson’s disaffected brother Tostig and was able to gather a sizeable fleet of hardened Viking warriors with which to invade England.

Harald Hardrada, the ‘Thunderbolt of the North’

Duke William of Normandy was a man who had lived his life in conflict. Having become Duke of Normandy at the age of 7 or 8, at least three of his guardians were murdered by ambitious rivals – one of these murdered in William’s own bed chamber. By his late teens William was successfully quashing rebellions and waging war against neighbouring regions such as Brittany and Maine. By 1066, after decades of warfare, he was one of the dominant forces in France and a warrior of renown, known for his strength and stamina as well as his tactical brilliance.

Statue of Duke William, later ‘the Conqueror’, in Falaise, Normandy

Therefore, following King Edward’s death, England quickly needed to find a leader who could defend it against these threats. What were the options for succession?

At this time English succession did not strictly follow primogeniture. Whilst sons of the last king were highly likely to inherit the throne, Anglo-Saxon kings were still elected by the Witan (a council of powerful noblemen). Setting aside the claims to the throne of Harald Hardrada and Duke William, the Witan had two basic choices; choose a successor from the ruling House of Wessex, or choose another powerful nobleman to become king.

Edward had no son, but there was a potential heir on the bloodline of the House of Wessex. Edgar Atheling was Edward’s great nephew. Edgar’s father, known as Edward the Exile, was the son of King Edmund Ironside who had been defeated by Cnut. Cnut had sent Edmund Ironside’s sons into exile and they ended up in Hungary. Edgar, son of Edward the Exile, was born in Hungary but had returned to England when King Edward had discovered that Edgar and his father still lived. Edward the Exile was seen as a potential heir to Edward the Confessor, but he died shortly after his return to England leaving his young son as the next in line to the throne. At the time of King Edward’s death, Edgar was still a child but he could potentially have been chosen by the Witan to be king.

When considering the election of a nobleman to become king, there was one obvious choice. Harold Godwinson was brother-in-law to the dead king. He was the biggest landowner in the country and had been an earl for many years already. He was described in the Vita Eadwardii (a contemporary biography of Edward the Confessor) as a wise man, and Orderic Vitalis (the English chronicler) describes him as intelligent and able. More than this, Harold already had a great military reputation of his own. Harold had fought successful campaigns against the Welsh in the 1050s and early 1060s. One of these campaigns involved a lighting, mounted raid into Wales in 1062 forcing the Welsh King Gruffydd to flee whilst Harold’s forces sacked his palace. Crucially, Harold also appears to have been in Normandy in 1064 where he campaigned alongside Duke William during a war against Brittany. He may therefore have been the man in England with the greatest insight into Norman battle tactics.

Bayeux Tapestry image of Harold meeting William in Normandy

It appears that the Witan did not vacillate for long. Harold’s coronation took place on the same day as King Edward’s funeral on 6th January 1066. This hasty coronation is seen by some as unseemly, but it should probably be seen as the act of a strong leader. Harold took the opportunity to secure the succession whilst all the powerful men of the country were already gathered for the funeral, thus preventing a succession crisis and making himself a clear point of command behind which the English could rally.

What then of his tactics when the moment to defend England came?

Harold had spent the Summer of 1066 guarding the South Coast of England with an army and a navy. He was well aware that the Normans were planning to invade and he mounted an appropriate defence. But the invasion didn’t come. From the point of view of the Norman fleet, the wind stubbornly blew in the wrong direction throughout the Summer. Autumn was approaching and convention dictated that a fleet would not risk crossing the Channel at that time of year due to the high chance of storms. The threat from Normandy seemed to have abated and the fyrd (the army conscripted from the peasantry of England) were allowed to return to the harvest.

Then came news of the Viking invasion in the North where Harald Hardrada had landed a fleet of several hundred ships. On 20th September his army engaged with the armies of the brother Earls Edwin and Morcar (earls of Mercia and Northumbria respectively), and defeated them at the Battle of Fulford.

Harold’s response to this was immense. He marched an army north so quickly that he took the Vikings completely by surprise and defeated them on 25th September at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, killing Harald Hardrada and his brother, Tostig Godwinson. It was whilst celebrating this victory in York that Harold learned that the winds across the Channel had changed and Duke William had finally landed. He reacted with characteristic decisiveness and covered the 190 miles to London in eight days. In London he would be well placed to make further strategic decisions, gather an army, and consult with other leaders. What should Harold do from there?

He had the option to bide his time. He could have spent more time in London and marched on at a later date, better rested and with a bigger army. Orderic Vitalis tells us that Harold’s brother, Gyrth, advised Harold to wait for just these reasons. Such a delay would have been bad news for the people of Sussex who would have been left undefended against the ravages of the Normans, but Sussex could have been sacrificed for the sake of the wider kingdom. The Norman chronicler, William of Poitiers, suggests that Harold acted in haste because he didn’t want to see Sussex suffer in this way. But Harold was a medieval king – he was not soft hearted. The decision to pause for just a day or two in London before he force-marched his army the 60 miles to Hastings must have been a tactical one, not a sentimental one.

We have seen that Harold had previously used rapid advances against an enemy to good effect – both in Wales and against Harald Hardrada. We have also seen that he was one of the few men in England who had seen how the Normans fought and this must also have informed his decision. At that moment, the Normans were encamped on a headland and Harold had a time-limited opportunity to bottle them up and hold them to battle. If he didn’t act then, the Normans would soon be riding their cavalry around England, ravaging the towns and villages, and outmanoeuvring English armies that mostly moved and fought on foot.

It is also probably a myth that Harold’s army arrived utterly exhausted at the battle. Whilst Harold and his closest household warriors had indeed marched the length of the country twice and fought a battle in the middle, the army around him had not. The fyrd system in England allowed armies to be rapidly raised from different regions of the country. Four separate armies were actually raised in England in 1066; one to guard the South coast, one to fight for Edwin and Morcar at Fulford, one to fight at Stamford Bridge, and a last to fight at Hastings. The men fighting at Hastings were mostly not those who had fought at Stamford Bridge. Most of them met Harold near to the site of battle having marched from their own homes in the south and east of England.

So, the forced march that is so often seen as an act of hubris, was a legitimate and defensible strategy. What’s more, it nearly worked. As an Englishman, it is agonising to read accounts of the battle and see how close it was to a different outcome. The English had formed their shield wall at the top of Senlac Hill. All day the Normans had attacked, on foot and on horse, and had been unable to break the line. It was late afternoon and the sun was sinking in the sky. If night fell then the fighting would stop. More English troops were on the way and the Normans were still trapped on the headland. If the battle ran to a second day, then a strengthened and revitalised English army would still have held the high ground against a battle-weary Norman force that had nowhere to retreat and no prospect of reinforcement. But, at dusk, the English line did break, Harold was killed and Duke William was on his way to becoming King William the Conqueror.

Bayeux Tapestry image of Harold dying at the Battle of Hastings

Nearly a millennium after his death, Harold’s reputation still bears the stains that were first put on it by Norman propagandists following the conquest. But, if Harold’s army had lasted an hour more at Hastings, he might have been one of our most celebrated national heroes – the king who saved England twice in under three weeks.